Thoracomyoplasty and perioperative negative wound pressure therapy for bronchopleural fistula after trans-sternal bronchial closure

Article information

A 62-year-old male complained of recurrent hemoptysis from a right-side pulmonary fungal ball (Figure 1). His right main pulmonary artery was accidentally sacrificed during a bilobectomy 10 years ago, and the remnant lung had a cavitary lesion. We performed trans-sternal transpericardial bronchial closure to avoid pneumonectomy through the infected thoracic cavity and to control the patient’s bloody cough [1]. The bronchial stump was closed using a surgical stapler and reinforced with Prolene sutures with felt pledgets. There were no postoperative complications, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 13. Two months later, a bronchopleural fistula developed at the bronchial stump (Figure 2). The patient had undergone video-assisted thoracosopic surgery irrigation and complete pneumonectomy (Figure 3) [2-4], and then dead spaces were obliterated via a thoracomyoplasty procedure and perioperative negative pressure wound therapy (Figure 4) [5]. The last outpatient follow-up was 1 year later. The wound remained clean, and the patient’s performance level was not impaired relative to his preoperative state. In the absence of standardized protocols for managing such patients, our reported case offers a review of these classic procedures that hybridize a minimally invasive technique with a tailored approach for each individual.

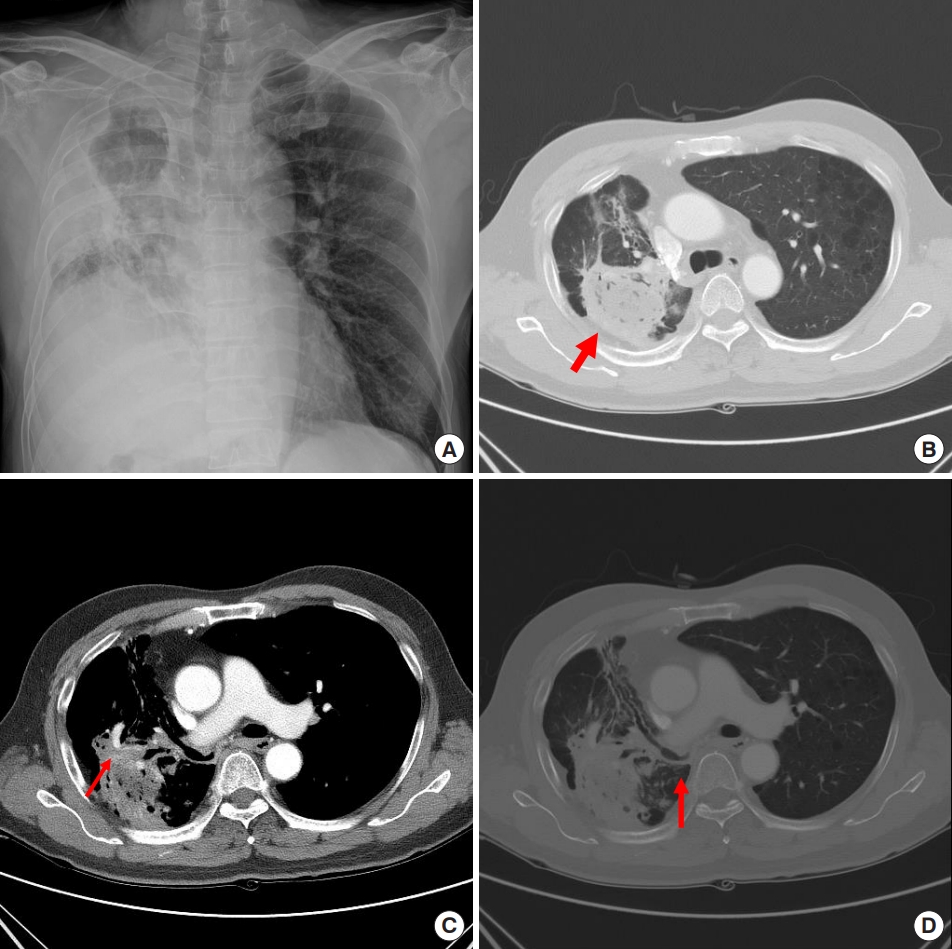

The chest images showed (A, B) the right-side fungal ball (red arrow) and (C) aneurysmal change of the bronchial artery (red arrow). (D) The right main pulmonary artery was divided with surgical material and only the right-side lower lobe bronchus was intact (red arrow).

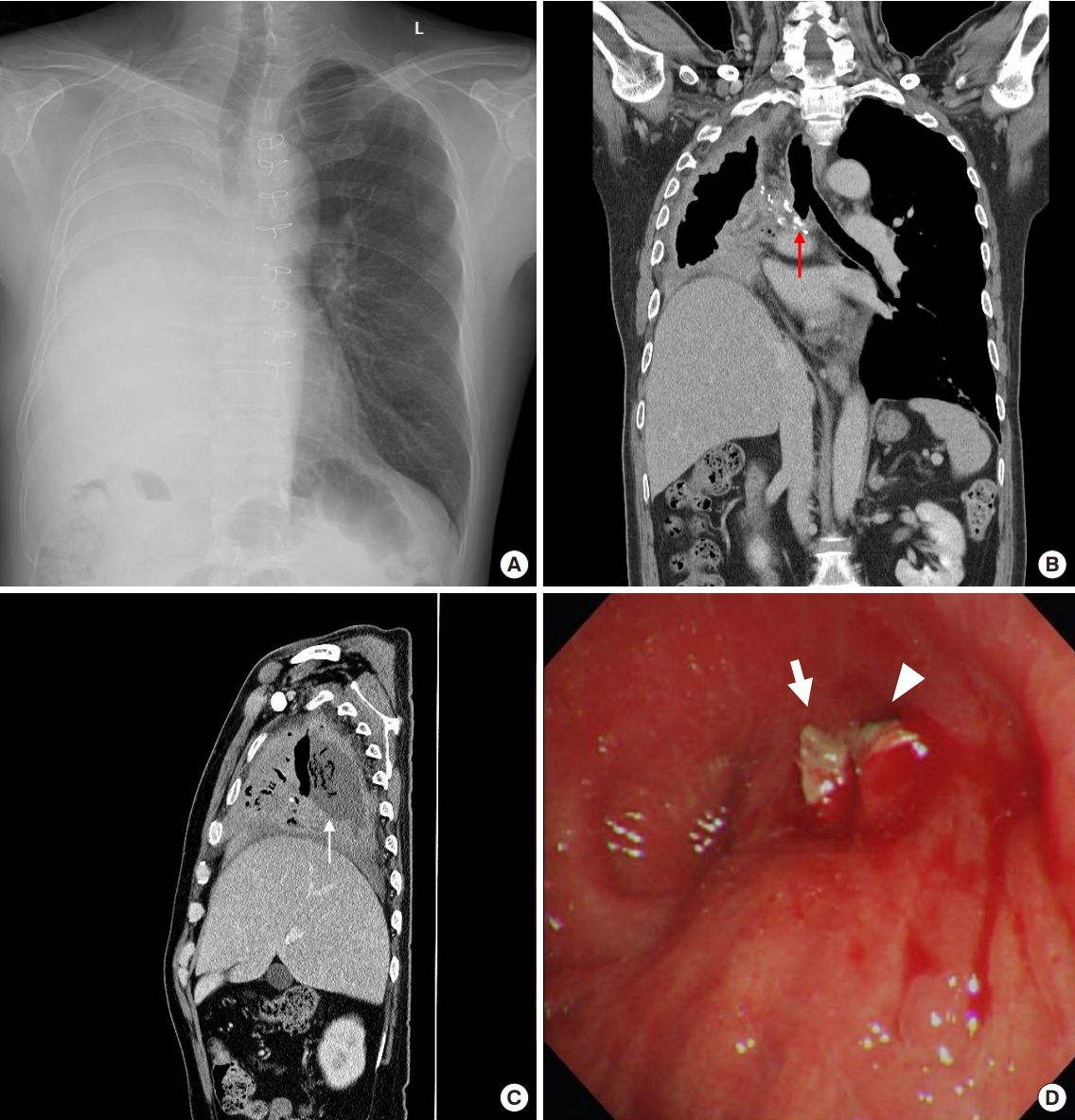

Two months after the trans-sternal bronchial division operation, the patient complained of a massive amount of purulent sputum. (A, B) The chest images showed a long right-side bronchial stump (red arrow) and cavitary change of the right-side thoracic cavity. (C) The fungal ball (white arrow) was still inside. (D) Bronchoscopy showed surgical material at the right-side bronchial stump (white arrow) and opening (arrowhead).

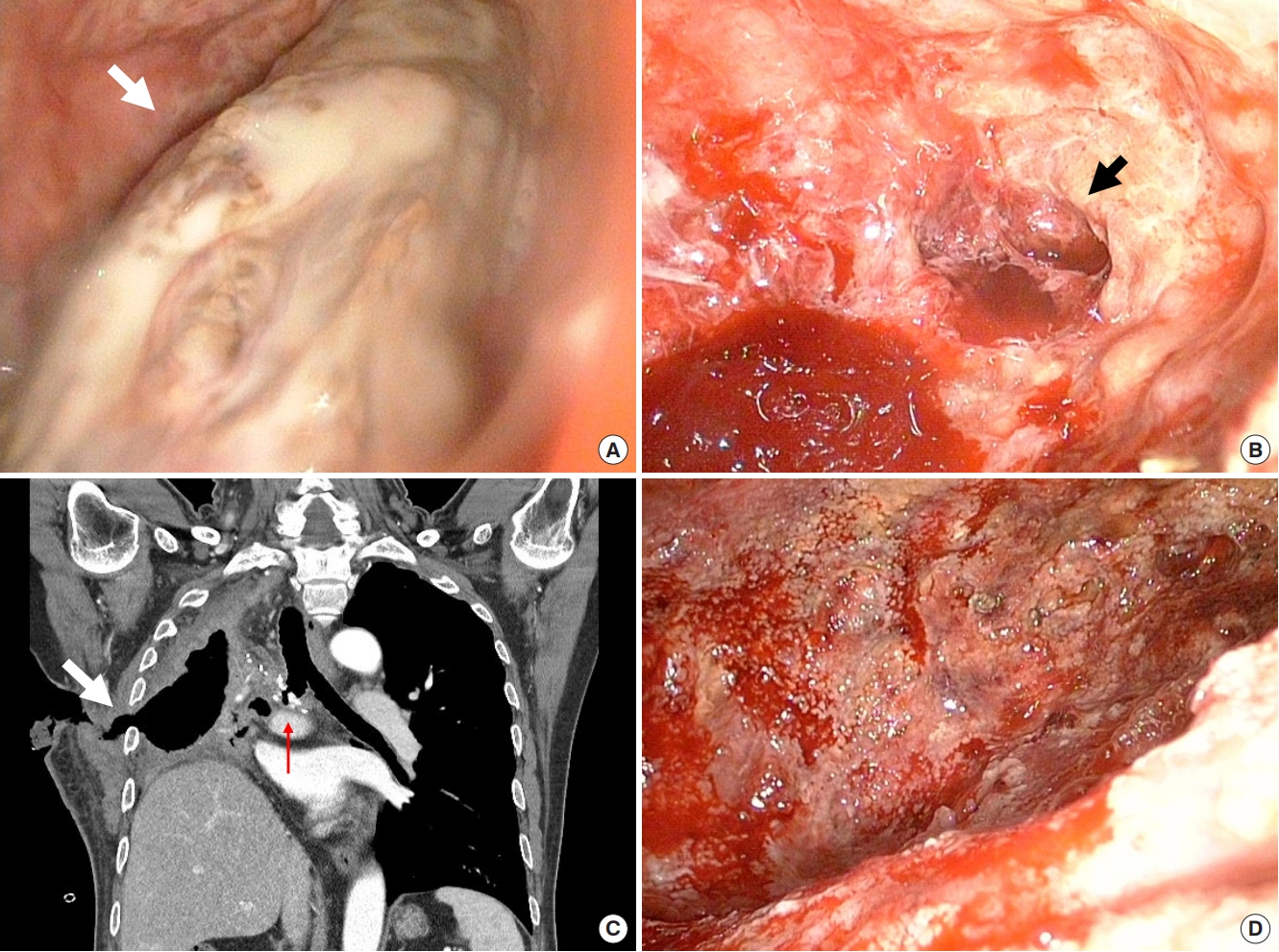

Video-assisted thoracoscopic exploration showed the fungal ball (white arrow) inside the right pulmonary cavity (A) and necrosis of the lung parenchyma (black arrow) after saline irrigation (B). (C) Chest computed tomography showed a bronchopleural fistula (red arrow) after trans-sternal trans-pericardial bronchial division and closure and an open wound (white arrow) of the chest wall after irrigation and drainage. (D) After exchanging a vacuum-assisted closure sponge under local anesthesia every 2 or 3 days, we performed follow-up pleural fluid culture every 3 days and found no bacterial growth.

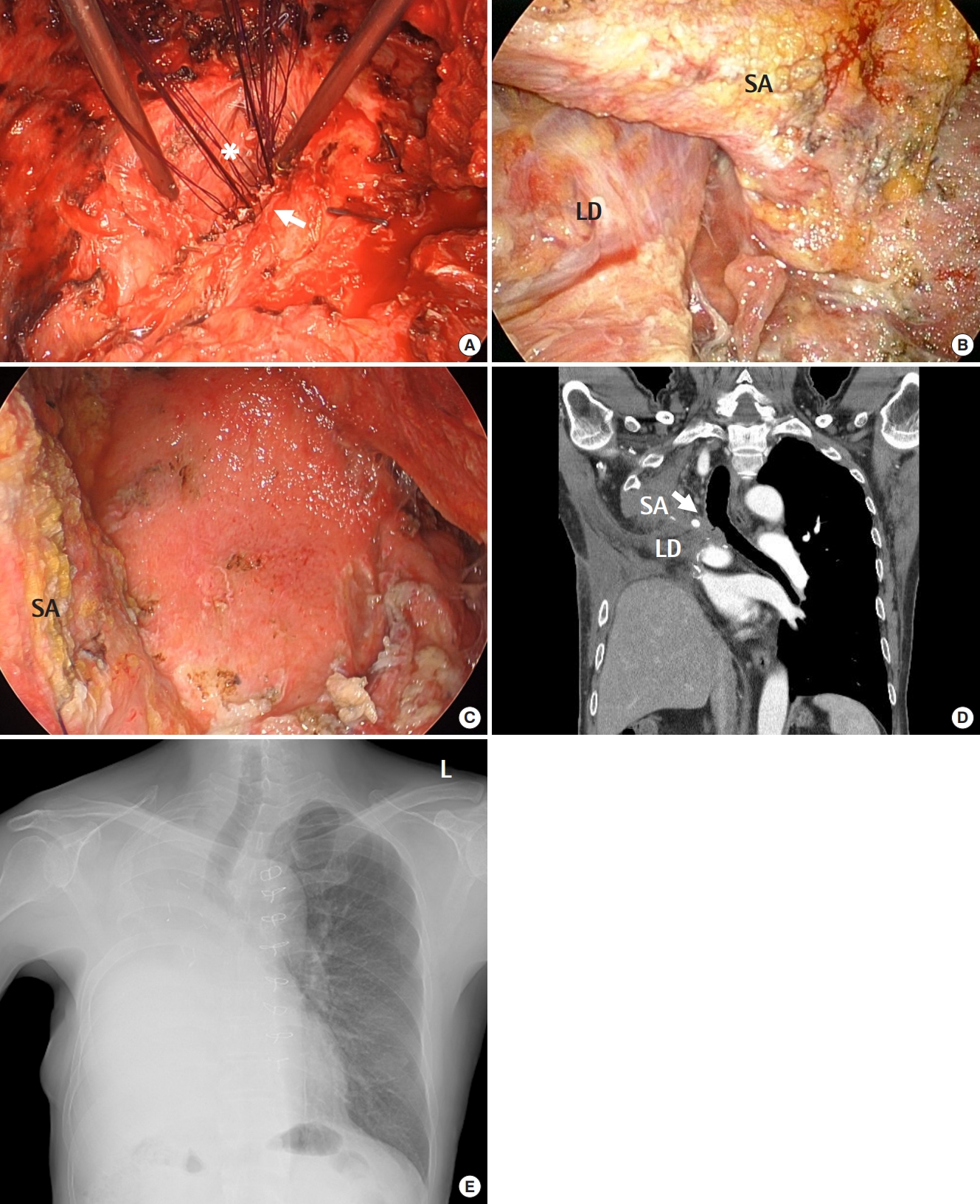

(A) After performing a complete pneumonectomy, we closed the bronchopleural fistula (white arrow) using multiple interrupted sutures (asterisk). (B) A serratus anterior muscle flap (SA) was used to cover the shortened bronchial stump, and the latissimus dorsi (LD) with intercostal muscles was transferred to pack the intrathoracic dead space. (C) On post-pneumonectomy day 10, we confirmed in the operating room that the pleural cavity was clean. (D) The postoperative chest computed tomography showed a shortened right-side bronchial stump covered by the pedicled SA and LD packed into the thoracic cavity (white arrow). (E) One year later, the patient visited the outpatient department without recurrence.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea University Ansan Hospital (IRB No. AS2021-0278) and written informed consent was waived.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: JH. Data curation: JIH. Formal analysis: JH. Methodology: JHK, Project administration: JSS, HJS. Visualization: JH. Writing–original draft: JIH, JH. Writing–review&editing: JH.