A Pilot Survey of Difficult Intubation and Cannot Intubate, Cannot Ventilate Situations in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background:

There have been no studies of airway management strategies for difficult intubation and cannot intubate, cannot ventilate (CICV) situations in Korea. This study was intended to survey devices or methods that Korean anesthesiologists and intensivists prefer in difficult intubation and CICV situations.

Methods:

A face-to-face questionnaire that consisted of a doctor’s preference, experience and comfort level for alternative airway management devices was presented to anesthesiologists and intensivists at study meetings and conferences from October 2014 to December 2014.

Results:

We received 218 completed questionnaires. In regards to difficult intubation, the order of preferred alternative airway devices was a videolaryngoscope (51.8%), an optical stylet (22.9%), an intubating laryngeal mask airway (11.5%), and a fiber-optic bronchoscope (10.6%). One hundred forty-two (65.1%) respondents had encountered CICV situations, and most of the cases were identified during elective surgery. In CICV situations, the order of preferred methods of infraglottic airway management was cricothyroidotomy (CT) by intravenous (IV) catheter (57.3%), tracheostomy by a surgeon (18.8%), wire-guided CT (18.8%), CT using a bougie (2.8%), and open surgery CT using a scalpel (2.3%). Ninety-eight (45%) of the 218 respondents were familiar with the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ difficult airway algorithm or Difficult Airway Society algorithm, and only 43 (19.7%) had participated in airway workshops within the past five years.

Conclusion:

The videolaryngoscope was the most preferred device for difficult airways. In CICV situations, the method of CT via an IV catheter was the most frequently used, followed by wire-guided CT method and tracheostomy by the attending surgeon.

Introduction

A difficult airway is defined as a situation in which trained doctors suffer from establishing endotracheal intubation and maintaining facial mask ventilation.[1] Difficult airway or cannot intubate, cannot ventilate (CICV) situations are rare but life-threatening.[2] To properly cope with these situations, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) and Difficult Airway Society (DAS) released practice guidelines for managing difficult airways.[1,3,4] Several airway devices have been introduced through these guidelines; however, the most optimal airway device has not yet been determined. In Canada, anesthesiologists’ proficiency and preferences in difficult intubation and CICV situations were surveyed in 2003 and then again in 2013.[5,6] The researchers concluded that in difficult intubations, the most frequently selected device was a videolaryngoscope, while in CICV situations, the most commonly chosen infraglottic airway management technique was a wire-guided cricothyroidotomy (CT) according to the 2013 survey.

This survey was important to highlight a current issue in clinical management; further clinical trials or interventions can be conducted using the background data. However, a comparable survey of difficult intubation and CICV has not yet been carried out in Korea. Therefore, this study investigated the devices or methods that Korean anesthesiologists and intensivists prefer to use in difficult intubations and CICV situations for future clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

This survey was administered at conferences of anesthesiologists and intensivists from October 2014 to December 2014. A questionnaire was provided by an anesthesiology resident using a face-to-face method. These residents had been trained to explain the devices and methods mentioned on the questionnaire, which consisted of three sections. The first proposed a situation where the anesthesiologists and intensivists would handle an unanticipated difficult intubation and failed direct laryngoscopy, and posed three questions. First, what were the first and second choices for alternative airway devices after a failed direct laryngoscopy? Second, had they ever used any of the listed devices on mannequins or patients before? Third, how comfortable were they in using the selected devices cited in the second question? The second section was related to a CICV situation. The respondents were asked how many times they had encountered a CICV situation in the last five years or ever, and in what circumstances they had encountered them. When the respondents considered surgical airway management after an intubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA) failed to sustain adequate ventilation, they were asked for their first and second choices, if they had ever used any of these methods and how comfortable they were with these methods. Finally, the respondents were asked how familiar were they with the ASA difficult airway algorithm and the DAS algorithm and if they had participated in any difficult airway workshops within the last five years. The third section included demographic questions.

We analyzed the data using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. For the statistical analysis, the clinicians’ comfort level with using alternative airway devices and performing surgical airway techniques were categorized into binary variables. “Very comfortable” and “somewhat comfortable” were combined into “comfortable,” while “somewhat uncomfortable” and “uncomfortable” were combined into “uncomfortable.”

Results

We gathered 218 questionnaires. The response rate was approximately 90%. However, some questionnaires were incomplete; blank responses were coded as missing data. The demographics of the respondents included age, sex, practice status, type of practice, and region of practice, and are described in Table 1.

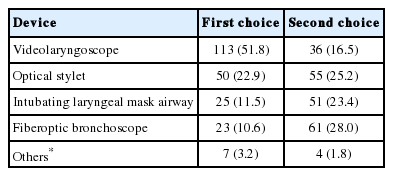

The first and second choices of alternative devices for difficult intubation situations are summarized in Table 2. The selection of the first-choice alternative device was also analyzed with consideration of the clinician’s practice level (resident or staff member). No relationship with the practice level was found for any of the devices except for ILMA. The tendency to choose an ILMA was more prevalent in the residents (residents vs. staff: 13.0% vs. 8.6%, chi-square test, p < 0.05). More than 80% of the respondents had used a videolaryngoscope, an optical stylet and an ILMA on patients and mannequins, while only 28.4% had experience with retrograde wire set intubation (Table 3). Anesthesiologists and intensivists who had previously worked with particular airway devices, such as asleep fiber-optic bronchoscope (FOB), ILMA, videolaryngoscope, optical stylet, and retrograde wire set intubation, had a correlation with the operator’s comfort. The respective proportions of comfort in the operators with experience vs. that in those without experience were as follows: asleep FOB: 51.5% vs. 19.6%; ILMA: 80.6% vs. 34.9%; videolaryngoscope: 94.8% vs. 36.0%; optical stylet: 93.2% vs. 40.2%; and retrograde wire stylet: 12.9% vs. 2.6% (chi-square, p < 0.05 for all comparisons).

Percentage having experience on patient and mannequin, and comfort with alternative devices by practice level

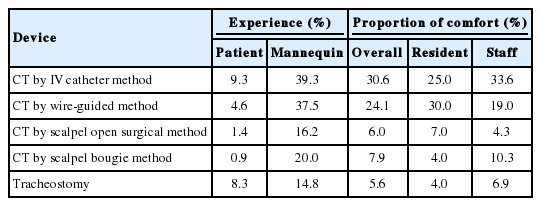

One hundred forty-two (65.1%) respondents had experienced a CICV situation an average of 2.6 times during his or her lifetime. One hundred twenty-six respondents (57.8%) had encountered such a situation within the last five years. Anesthesiologists and intensivists reported CICV in the following situations: elective surgery, 44.0%; emergency surgery, 30.3%; head and neck surgery, 26.6%; trauma, 15.1%; obstetrics, 7.8%; intensive care unit patients, 6%; emergency department patients, 3.7%; bariatric patients, 2.8%; and burn patients, 2.3%. The first and second choices for an infraglottic airway are summarized in Table 4, and the experiences and proportions of comfort with an infraglottic airway are shown in Table 5. Less than 10% of the respondents had experience applying infraglottic airway techniques in actual patients. Most participants were uncomfortable with infraglottic airway techniques, including the open surgical CT method (6.0%), the bougie CT method (7.9%), and tracheostomy (5.6%), which were all less than 10%. The proportions of comfort in each of the infraglottic airway techniques were not significantly different between residents and staff.

Percentage having experience with infraglottic airway techniques on mannequins and patients, and comfort with infraglottic airway devices among residents and staffs

Forty-five percent of our respondents were familiar with the ASA difficult airway algorithm or the DAS algorithm. However, only about 20% had participated in a difficult airway workshop in the past five years. Training obtained from difficult airway workshops was related to participants’ familiarity with the ASA difficult airway algorithm or the DAS algorithm, but was not associated with the choice of difficult airway devices or infraglottic airway techniques.

Discussion

In this study, more than half of the anesthesiologists and intensivists preferred a videolaryngoscope (51.8%) as their first-choice device in difficult intubation situations, followed by an optical stylet (22.9%). In a 2013 Canadian survey, most of the anesthesiologists (89.6%) also selected a videolaryngoscope as their first alternative airway device; according to an earlier survey published in Canada in 2005, the use of a lighted stylet, FOB, ILMA, a retrograde wire set, and a flexible tip has largely replaced the videolaryngoscope for this procedure. Optical stylets were more often preferred in this survey than in the Canadian survey from 2013 (22.9% vs. 1.7%). This discrepancy also might have resulted from the different participants of the respective studies. This questionnaire was designed for anesthesiologists and intensivists, while the Canadian survey of 2013 included only one anesthesiologist.[7,8] Other studies have demonstrated that before performing the procedure on actual patients, clinicians should practice using bronchoscopy simulation training to accelerate the acquisition of bronchoscope skills; the use of an endobronchial ultrasound simulator has also been reported to lead to a more rapid acquisition of skills.[9-11] Similar findings were observed in this study. Many experiences were proportional to the physician’s comfort level in using difficult airway devices, except for awake FOB. In addition, the order of comfort level in using difficult airway devices was the same as the order of first-chosen difficult airway devices.

In the 2005 Canadian survey, a CT using an intravenous (IV) catheter was the most popular technique. However, wire-guided CT (39.3%) was the most frequently used in the 2013 Canadian study, followed by CT and IV (27.9%) and a tracheostomy performed by the surgeon (22.5%). In our study, a CT using an IV catheter (57.3%) was the most chosen, and a wire-guided CT (18.8%) and a tracheostomy by the surgeon (18.8%) followed. CT by an IV catheter takes a short time and creates very few serious complications because it does not require any sophisticated equipment.[12] However, the airflow to the lungs is limited by the diameter of the catheter, so CT using an IV catheter is inferior to a wire-guided CT method and a tracheostomy at providing adequate ventilation. Thus, we predicted that the trend in Korea will move from CT using an IV catheter to CT using a wire-guided method, as was noted in Canada.

The probability of encountering a CICV situation in this study was similar to that from the 2013 Canadian survey. However, the degree of experience and proportion of comfort were relatively low in all methods, while the number of participants who took part in difficult airway workshops within the last five years were smaller in our study than in the Canadian study (about 50% vs. 20%, respectively). Insufficient education and training regarding airway management accounted for about 50% of airway complications that arose.[13] For example, in a previous study, even when an experienced anesthesiologist used the Glidescope® (Verathon, Seattle, WA, USA) videolaryngoscope, significant adverse outcomes resulted when these practitioners lacked familiarity with the instrument.[14] As technology continues to advance, computer aided simulators and mannequins create more realistic situations;[15] therefore, it is necessary to utilize this equipment to augment proficiency in airway management.

There were some limitations in this survey. Most of our results were obtained from younger doctors (under age 45 at 76%). This survey was designed for anesthesiologists and intensivists; however, the distribution of respondents was not investigated. An unrepresentative population of respondents might have influenced the different results in this survey compared with a Canadian survey of 2013. Since we had no choice but to reduce the cost and increase the response rate, the survey was conducted using a face-to-face method and was designed as a pilot survey. Therefore, most respondents worked in specific geographic areas, particularly at teaching hospitals. In addition, we did not consider the presence or availability of the aforementioned devices in each hospital, which might also have affected their use. Therefore, a larger survey that is more representative of the practices and techniques of anesthesiologists and intensivists in Korea should be conducted to confirm our results.

In summary, our survey revealed that a videolaryngoscope was the first choice in difficult intubation situations, and an optical stylet was next. Experiences with particular airway devices, such as asleep FOB, ILMA, videolaryngoscope, optical stylet, and retrograde wire set intubation, had a correlation with the comfort level of the operator. In CICV situations, 65.1% of the respondents had experienced these situations, and CT using an IV catheter was the most preferred method, followed by wire-guided CT and then tracheostomy by the surgeon. In addition, simulation training might be effective at improving the operators’ comfort level with these different devices for difficult intubation.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an Inha University Grant.