Abdominal compartment syndrome in critically ill patients

Article information

Abstract

Intra-abdominal hypertension can have severe consequences, including abdominal compartment syndrome, which can contribute to multi-organ failure. An increase in intra-abdominal hypertension is influenced by factors such as diminished abdominal wall compliance, increased intraluminal content, and certain systemic conditions. Regular measurement of intra-abdominal pressure is essential, and particular attention must be paid to patient positioning. Nonsurgical treatments, such as decompression of intraluminal content using a nasogastric tube, percutaneous drainage, and fluid balance optimization, play crucial roles. Additionally, point-of-care ultrasonography aids in the diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal hypertension. Emphasizing the importance of regular measurements, timely decompressive laparotomy is a definitive, but complex, treatment option. Balancing the urgency of surgical intervention against potential postoperative complications is challenging.

INTRODUCTION

In critically ill patients, intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) frequently manifest as consequences of interventions such as intubation and fluid resuscitation. Notably, 25% of patients in intensive care units (ICUs) are affected by these conditions. Moreover, previous studies indicate that over half of these patients encounter IAH within the initial week of their ICU admission [1,2]. Under these circumstances, the timely diagnosis of IAH is crucial. If overlooked, IAH can evolve into ACS, which could subsequently result in organ dysfunction. This progression significantly affects the prognosis of critically ill patients. Reintam Blaser et al. [3] reported that during the initial 2 weeks of ICU admission, the presence and severity of IAH independently elevated both the 28- and 90-day mortality rates, with mortality surging to 38.6% when ACS manifested. Recognizing ACS early based on clinical indicators and risk factors can dramatically decrease the associated complications and mortality rates. Timely detection of these clinical signs allows for immediate emergency laparotomy to relieve the pressure. However, in practical clinical settings, measuring intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) in critically ill patients presents challenges. Although IAP’s frequency has decreased, deterioration due to IAP still occurs in approximately 3%–5% of patients [4].

In this review, we discuss the measurement of IAP, risk factors for IAH, and compartment syndrome. In 2013, the World Society of Abdominal Syndromes published the updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines for IAH and ACS. Since then, IAH and ACS treatments have been developed and revised based on these guidelines. Based on these guidelines, we provide further insights into early detection, preventive therapeutic measures, and definitive treatments when these conditions manifest.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

Relevant articles were obtained through comprehensive searches of the Medline PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Databases for the period ending 24 June, 2023. These databases were searched using keywords such as (Intra-abdominal pressure) OR (Intraabdominal pressure) OR IAP OR (Intra-abdominal hypertension) OR (Intraabdominal hypertension) OR IAH OR (abdominal compartment syndrome) OR ACS OR (intra-abdominal pressure measurement) OR (intraabdominal pressure measurement).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In individuals without pathological conditions, IAP is 0 mm Hg. During standard respiratory functions, positive pressure ventilation exerts a direct impact on IAP. Baseline IAP is 5 mm; but certain conditions, including coughing, obesity, and pregnancy, elevate the baseline. Notably, the factors that increase IAP can be categorized into five distinct groups: (1) Elasticity of abdominal wall and diaphragm (diminished abdominal wall compliance), (2) Increased intraluminal content, (3) Increased abdominal content, (4) Systemic condition causing capillary leak/fluid resuscitation, (5) Underlying causes.

The risk factors associated with each of these categories are detailed in Table 1. Compliance is forcibly restricted by mechanical ventilation, resulting in an IAP nearly double that of patients with spontaneous breathing [3]. Additionally, among the intra-abdominal organs, the movable wall area is confined to the abdominal wall and diaphragm [5]. The elasticity of abdominal lesions is notably reduced and compromised after surgical intervention [5-7] in which there is a reduction in the intra-abdominal volume domain, which could significantly influence its effects [8].

Within the intra-abdominal compartment, the viscera play a predominant role in influencing pressure dynamics. The dimensions of the bowel, coupled with the volume of its intraluminal content, can significantly affect pressure. Interventions during resuscitation, particularly extensive fluid resuscitation, can cause capillary leakage. This, in conjunction with fluid resuscitation-induced systemic alterations, can contribute to an escalation in IAP [9,10]. Considering potential underlying etiologies is imperative. In patients presenting with elevated IAP attributable to underlying etiologies, there is an inherent predisposition toward the development of ACS.

DIAGNOSIS

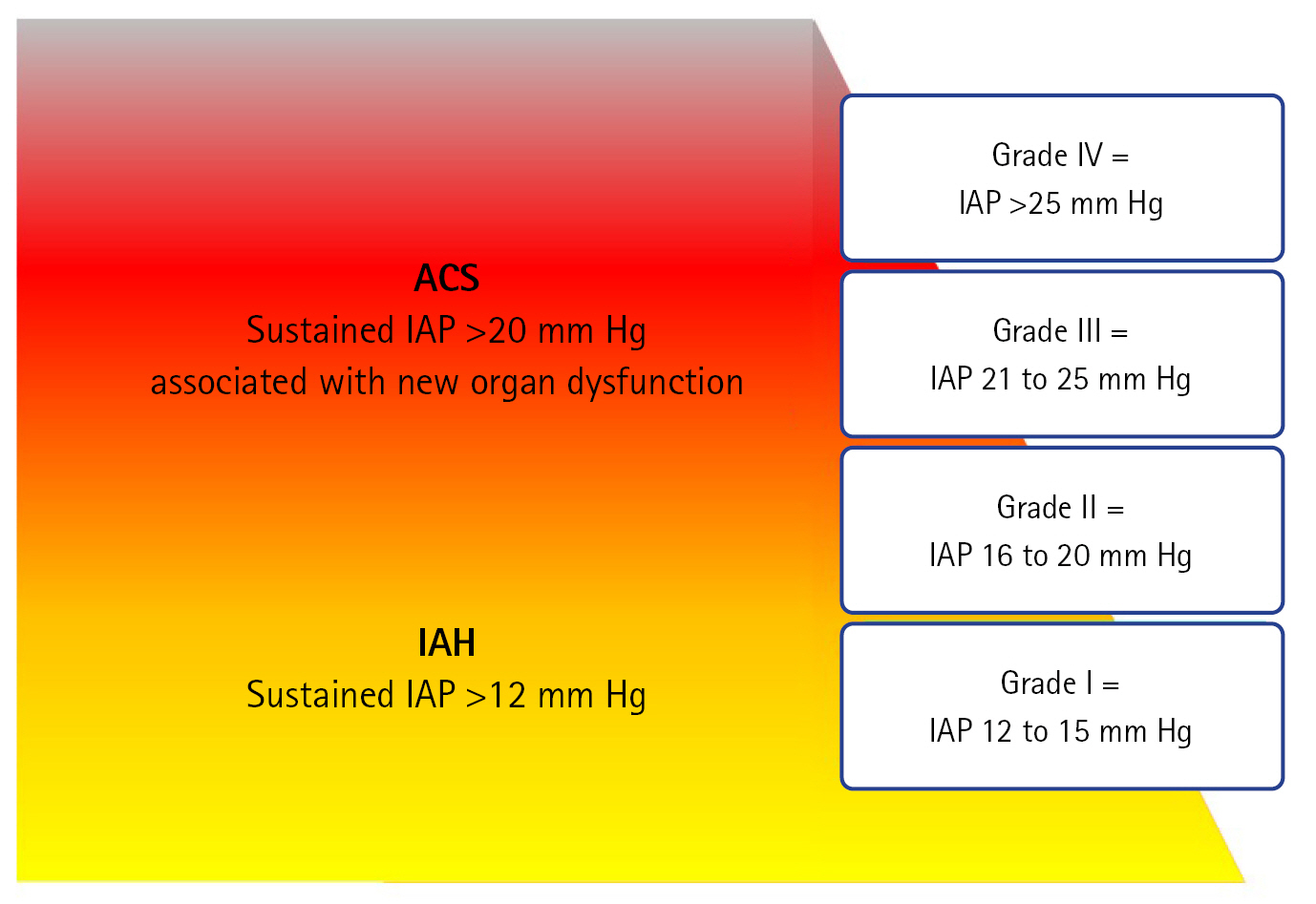

Monitoring IAP is crucial for detecting the risk of ACS escalation. In patients undergoing treatment, early signs of IAH should be identified using IAP measurements before these signs manifest as organ failure or other symptoms. Although IAH grading is not an absolute criterion, higher IAH grades are associated with higher mortality rates [11]. In addition to IAP monitoring, early recognition of ACS through clinical signs and risk factors can significantly reduce the associated morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, IAP monitoring is essential for ICU patients with risk factors.

MEASUREMENTS

Bladder pressure measurement is a straightforward and minimally invasive technique for reliably estimating IAP. This method relies on the principle that changes in IAP are reflected in intravesical pressure. As 90% of patients in the ICU are equipped with a Foley catheter, this allows for convenient measurement directly during Foley insertion without the need for additional invasive procedures. The IAP is recorded in mm Hg. Care should be taken to avoid measurement during moments when IAP may acutely increase due to actions such as sneezing, laughing, shouting, coughing, or performing the Valsalva maneuver. Measurements should be made at the end of expiration with the patient in a supine position. The transducer needs to be zeroed at the level of the mid-axillary line, and the patient needs to be free from abdominal muscle contractions caused by conditions such as peritonitis (Figure 1) [12,13].

Understanding that the definition of ACS does not rely solely on the absolute values of IAP is crucial. Instead, the diagnosis of IAH should always be considered in conjunction with the potential for new organ dysfunction. Even if patients with IAH exhibit the same IAP levels, the risk of ACS can vary significantly owing to individual variables, such as blood pressure and abdominal wall compliance. Factors such as pregnancy, cirrhosis with ascites, and severe obesity can influence abdominal wall compliance, and consequently, the likelihood of ACS [12].

Abdominal perfusion pressure (APP) has been proposed as a more accurate predictive variable of visceral perfusion and a better endpoint for resuscitation than either IAP or mean arterial pressure alone. APP is the value obtained by subtracting IAP from mean arterial pressure (APP=mean arterial pressure–IAP). However, although there is evidence suggesting that APP may be a more accurate predictor of visceral perfusion and, potentially, a better endpoint for resuscitation than IAP or MAP alone, relevant randomized controlled trials or meta-analyses supporting this view conclusively are lacking. The observational studies available are predominantly of low quality due to bias and indirectness and mainly involve heterogeneous populations of ICU patients. These studies suggest that a reduced APP may be a poor independent prognostic factor, but the effects of interventions to improve APP on clinical outcomes are unclear. Therefore, the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (WSACS) withheld a recommendation on the use of APP in managing critically ill or injured patients until further high-quality interventional trials are conducted [12].

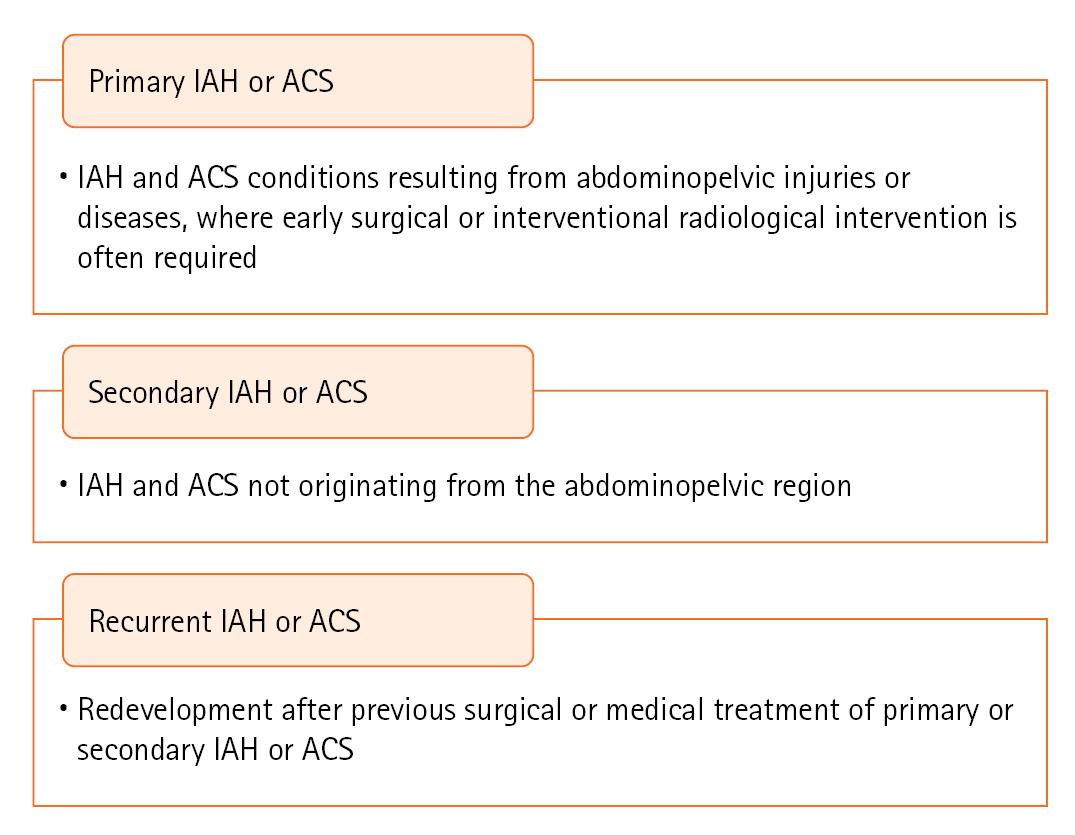

PRIMARY IAH OR ACS DEFINITIONS

Definitions of primary, secondary, and recurrent IAH or ACS are shown in Figure 2. These typically arise from direct abdominal trauma, abdominal surgery, mass-like lesions, or other causes of ascites. Secondary IAH or ACS originate from non-abdominal or non-pelvic sources, such as massive fluid resuscitation, major burns, or elevated IAP due to sepsis. Recurrent IAH or ACS refers to the re-emergence of elevated IAP after treatment in any given situation.

IAH ASSESSMENT: INFLUENCE OF RISK FACTORS

Although the causes of increased IAP can be categorized into four distinct groups, noting that elevated IAP is rarely caused by a single factor is important. Considering that multiple factors often interact in a complex manner, considering their multifaceted nature when developing treatment plans is essential. Risk factors and their corresponding references are detailed in Table 1 [14-38].

PROGRESSION OF IAH TO ACS AND ITS IMPACT ON VARIOUS ORGANS

An increase in IAP can lead to IAH and ACS, both of which can result in organ failure. This can manifest as both cause and consequence. Extensive research is currently underway to understand the far-reaching effects of elevated IAP. Isolated, transient elevation in IAP is seldom associated with significant organ failure in patients [39]. Persistent IAH can progress to organ failure. ACS is characterized by the onset of organ dysfunction due to a sustained increase in IAP. ICU patients with IAH commonly transition to multi-organ dysfunction not solely from elevated IAP, but also from other concurrent factors, such as sepsis. Therefore, monitoring IAP consistently to determine IAH persistence is essential. Distinguishing between organ dysfunction caused by IAH and that from other causes is crucial. Multi-organ dysfunction resulting from ACS progresses at an alarmingly rapid rate. However, the prompt resolution of ACS offers an opportunity to reverse these catastrophic outcomes [40]. In critically ill patients, rigorous and continuous monitoring of IAP is necessary to predict potential organ dysfunction attributable to IAH.

IMPACT ON THE KIDNEYS

Although ACS affects a multitude of organs, the kidneys are most often affected. This is largely because changes in kidney function are readily reflected as a decrease in urine output. Most initial treatments for acute kidney injury involve aggressive volume replacement, which significantly contributes to elevated IAP [41,42].

IMPACT ON THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

The respiratory system is also significantly affected. IAH induces a decrease in lung volume, which further impairs thoracic wall compliance [18]. Additionally, independent risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia were identified. Papakrivou et al. [43] found that the bacterial strains detected in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia and IAH were predominantly intestinal flora, Klebsiella, Proteus mirabilis, and Escherichia coli. In contrast, in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia and normal IAP, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Staphylococcus aureus were mainly detected. This suggests the possibility of bacterial translocation in patients with IAH.

IMPACT ON CIRCULATION

IAH significantly affects hemodynamics. An increase in IAP elevates intrathoracic pressure and impedes venous return from the inferior vena cava. Additionally, an increase in abdominal pressure inherently increases afterload and results in a decrease in stroke volume. This leads to an increase in end-diastolic pressure, which, in turn, diminishes cardiac filling. The outcome is a reduction in systemic cardiac output, manifesting as decreased blood pressure and impaired circulation [44,45].

IMPACT ON INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

IAH reduces the backflow of the venous plexus into the spinal canal. An increase in intrathoracic pressure elevates the central venous pressure, leading to diminished venous circulation through the jugular vein. This increases intracranial pressure [46,47].

IMPACT ON GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT AND HEPATOBILIARY SYSTEM

Functions of the intestine and liver are also affected by IAH. An increase in abdominal pressure directly affects the intestine, reducing splanchnic perfusion. Consequently, intestinal permeability increases, leading to mucosal barrier failure. This can trigger bacterial translocation, potentially causing organ failure [48]. Additionally, IAH leads to decreased gastrointestinal motility [49]. This reduced motility, both a cause and effect, can induce conditions such as ileus, which can further exacerbate IAH. Effects on the biliary system were also assessed. With the onset of IAH, there is a significant reduction in blood flow to the portal vein and inferior vena cava along with an increase in pressure. As a result of this sustained impact, cell damage and reparative responses can be observed in the liver [50,51]. While organ failures can occur individually, they often manifest in a multi-organ fashion [52].

TREATMENT AND MONITORING

Periodic measurement of IAP in patients at risk of ACS in the context of IAH is crucial. In addressing IAP monitoring for ICU patients, we suggest a strategy with nuances that account for the presence and number of risk factors related to IAH and ACS. The WSACS does not universally mandate IAP monitoring for all ICU patients but does stress its importance in those with identifiable risk factors for IAH/ACS. The WSACS does recommend the use of the trans-bladder method for accurate IAP measurement and a protocolized approach to monitoring and management to enhance patient outcomes.

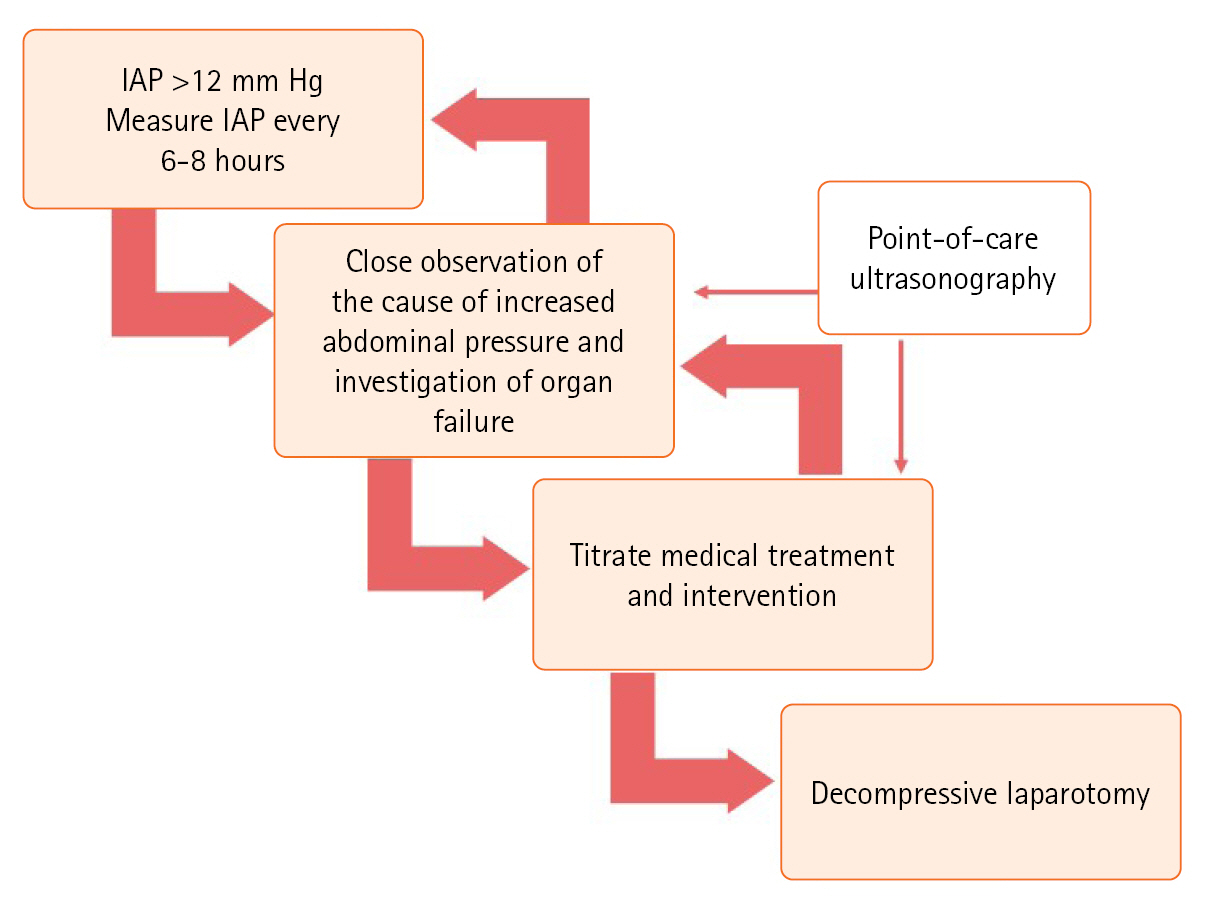

We recommend IAP monitoring for any ICU patient showing at least one known risk factor for IAH/ACS. This is based on the understanding that presence of a single risk factor significantly increases the risk of IAH/ACS, thus necessitating early and careful monitoring. Furthermore, in patients with two or more risk factors for IAH/ACS, we propose an enhanced level of IAP monitoring. This is due to the compounded risk from multiple factors and demands a more comprehensive monitoring strategy for prompt detection and effective intervention. This proactive approach is vital to reduce the incidence and impact of these conditions. Titration of medical treatments and interventions is of paramount importance (Figure 3).

Management of intra-abdominal hypertension/abdominal compartment syndrome. IAP: intra-abdominal pressure.

The principle of this treatment is associated with five therapy categories that address factors that increase IAP. Recognizing patients in the early stages of low-grade IAH (i.e., grades I and II) allows for the prevention of and response to ACS through non-surgical treatments. However, regardless of the grade, the duration of IAH can directly affect a patient's prognosis, especially when IAH with organ failure occurs. Therefore, correction is crucial in such situations [39]. Close observation during these processes and the verification of organ failure are vital.

ELASTICITY OF ABDOMINAL WALL AND DIAPHRAGM (DIMINISHED ABDOMINAL WALL COMPLIANCE)

Appropriate sedation and analgesia may be beneficial for pain control. The efficacy of neuromuscular blockade in relation to the elasticity of the abdominal wall and diaphragm has been established [53]. However, continuous use of neuromuscular blockade is challenging. In De Laet's study [53], although neuromuscular blockade demonstrated a temporary reduction in IAP, definitive results in improving patient urine output or survival rates were not achieved. Therefore, neuromuscular blockade should be considered for treatment as a bridge to decompressive laparotomy. For patients with burns, escharotomy has been confirmed to improve the elasticity of the abdominal wall and alleviate ACS [54,55]. During treatment, this procedure should be considered alongside decompressive laparotomy.

INCREASED INTRALUMINAL AND ABDOMINAL CONTENT

In patients with underlying diseases or an increased volume of intraperitoneal fluid due to fluid therapy, temporary relief from elevated abdominal pressure can be provided through methods such as percutaneous drainage before resorting to resuscitative laparotomy [56]. From the initial stages of such non-invasive treatments, the recent addition of point-of-care ultrasonography to treat IAH is also crucial. The use of point-of-care ultrasonography for diagnostic and therapeutic approaches can be holistically applied to IAH treatment. Pereira et al. [36] used this for the initial treatment of patients with IAH/ACS. This procedure aided in adjusting the position of the nasogastric tube in the pyloric area to facilitate drainage and in assessing bowel movements and the need for further interventions, such as an enema. Percutaneous decompression can be considered by verifying the amount of intra-abdominal fluid (Figure 3).

SYSTEMIC CONDITION DUE TO CAPILLARY LEAK OR FLUID RESUSCITATION

By performing inferior vena cava and cardiac echography, the degree of fluid overload and cardiac function can be approached by adjusting the patient's fluid balance accordingly. The World Society of Abdominal Syndromes management algorithm recommends checking intraluminal contents, verifying the degree of abdominal wall compliance improvement, and confirming renal hepatic artery and portal-venous blood flow perfusion. Additionally, early veno-veno hemofiltration reduces IAP and diminishes the decline in organ function [57].

Cheatham et al. [35] demonstrated a significant elevation in IAP when subjects were in a supine position compared to a 30° head elevation. While the study did not elucidate the impact of these measurements on organ failure beyond a simple increase in values, the findings did indicate that measurements taken other than in the supine position might not reflect the true values accurately. This suggests that there may be a need to re-evaluate IAP measurements when the head is elevated. Furthermore, in IAH, the passive leg raising test, which is used to anticipate a patient's fluid response, can produce many false negatives. Therefore, verification and caution are needed when treating shock [58,59].

DECOMPRESSIVE LAPAROTOMY

When ACS occurs, the most definitive treatment method, decompressive laparotomy, must not be delayed. In such cases, an open abdomen may be a therapeutic option. Among the rescue therapy methods for an open abdomen, negative wound therapy, which is commonly implemented, has been reported to have minimal impact on IAP measurements [60]. Although surgical intervention remains the definitive solution for certain clinical conditions, many patients may not be hemodynamically stable for immediate surgery. The rapid restoration of systemic perfusion following open abdominal procedures is essential. However, prolonged maintenance of an open abdomen can lead to postoperative complications.

Furthermore, the resuscitation phase after open surgery does not always lead to immediate recovery. There may be instances in which extensive fluid resuscitation is required for a certain period, leading to deliberations regarding the timing of abdominal closure. Nonetheless, once the primary treatment goal is accomplished, prompt closure of the abdominal wall (including the fascia) should be attempted because of the potential complications and increased difficulty of future closures. However, care is needed as forcing fascial closure can increase the risk of ACS recurrence. In some cases, the abdomen may close while the fascia is excluded. This can lead to herniation. Alternatively, subsequent surgery may be required. This could involve applying a mesh or separation and suturing of the abdominal fascia along the midline to reconstruct the abdominal wall [61].

CONCLUSIONS

IAH presents multifaceted challenges in patient care and has the potential to progress to life-threatening ACS. Regular monitoring of IAP, interventions aided by point-of-care ultrasonography, and timely decompressive laparotomy are pivotal for mitigating the associated risks and ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

KEY MESSAGES

▪ Intra-abdominal hypertension can progress to critical abdominal compartment syndrome and significantly contribute to multi-organ failure.

▪ Close observation and an understanding of the factors that cause increased abdominal pressure are crucial.

▪ Regular intra-abdominal pressure measurements combined with timely assessment of potential organ failure are essential, emphasizing the importance of tailoring medical treatments and interventions.

▪ Balancing non-surgical treatments with the need for surgical intervention, particularly decompressive laparotomy, is a primary challenge in the care of patients at risk of intra-abdominal hypertension due to abdominal compartment syndrome.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dowan Kim is an editorial board member of the journal but was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: HJ,. Methodology: NL, JK. Formal analysis: EJ. Data curation: HJ, NL. Visualization: HJ, YP. Project administration: DK. Writing–original draft: HJ. Writing–review & editing: HJ, DK, YP, YJ.

Acknowledgements

None.