Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Acute Crit Care > Volume 37(4); 2022 > Article

-

Review Article

Basic science and research Barriers and facilitators in the provision of palliative care in adult intensive care units: a scoping review -

Christantie Effendy1

, Yodang Yodang2

, Yodang Yodang2 , Sarah Amalia3

, Sarah Amalia3 , Erna Rochmawati3

, Erna Rochmawati3

-

Acute and Critical Care 2022;37(4):516-526.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4266/acc.2022.00745

Published online: October 18, 2022

1Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

2School of Nursing, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Universitas Sembilanbelas November Kolaka, Kolaka, Indonesia

3School of Nursing, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Corresponding author: Erna Rochmawati Erna Rochmawati, School of Nursing, Graduate Program, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Jl Brawijaya, Tamantirto, Kasihan, Bantul, D.I Yogyakarta 55183, Indonesia Tel: +62-2-7438-7656 Fax: +62-2-7438-7656 E-mail: erna.rochmawati@umy.ac.id

Copyright © 2022 The Korean Society of Critical Care Medicine

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

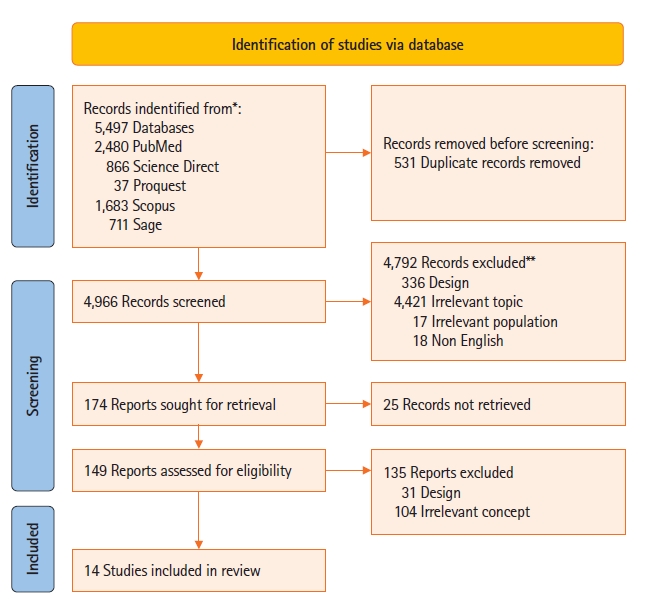

- The provision of palliative care in the intensive care unit (ICU) is increasing. While some scholars have suggested the goals of palliative care to not be aligned with the ICU, some evidence show benefits of the integration. This review aimed to explore and synthesize research that identified barriers and facilitators in the provision of palliative care in the ICU. This review utilized Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Scoping Review guidelines based on population, concept, and context. We searched for eligible studies in five electronic databases (Scopus, PubMed, ProQuest, Science Direct, and Sage) and included studies on the provision of palliative care (concept) in the ICU (context) that were published in English between 2005–2021. We describe the provision of palliative care in terms of barriers and facilitators. We also describe the study design and context. A total of 14 papers was included. Several barriers and facilitators in providing palliative care in the ICU were identified and include lack of capabilities, family boundaries, practical issues, cultural differences. Facilitators of the provision of palliative care in an ICU include greater experience and supportive behaviors, i.e., collaborations between health care professionals. This scoping review demonstrates the breadth of barriers and facilitators of palliative care in the ICU. Hospital management can consider findings of the current review to better integrate palliative care in the ICU.

INTRODUCTION

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Charting the data

RESULTS

Lack of capabilities

Family boundaries

Practical issues

Cultural differences

Supportive behaviors

Previous experiences

DISCUSSION

CONCLUSIONS

KEY MESSAGES

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: CE, YY, ER, Data curation: ER, SA. Formal analysis: ER, SA. Funding acquisition: ER. Methodology: CE, YY, ER. Project administration: SA. Writing–original draft: all authors. Writing–review & editing: all authors.

NOTES

Acknowledgments

| Study | Purpose | Design |

Context |

Respondent |

Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Type of ICU | Characteristics | Total | ||||

| Santos et al. (2017) [17] | To explore perceptions of health professional related with end-of-life care and discuss they goals when planning a palliative care | Qualitative approach | Brazil | Oncology ICUs | Nurses (n=12), physicians (n=8), nutritionists (n=2), and physiotherapists (n=3) | 25 Professionals participated | Barriers doing palliative care in oncology intensive care unit consist of prognostic disease of patient, lack of knowledge and interest in palliative care and reluctance to accept that it is no longer possible to keep seeking for a cure |

| Espinosa et al. (2010) [18] | To understand the experience of ICU nurses in providing end of life care is important first step to improving terminal care in the ICU | Phenomenological research study | United States | Adult ICUs | Participants consisted of women (n=15) and men (n=3) of nurses and with experience providing terminal care | 18 Nurses | Lack of involvement, education, experience of nurses in the plan of care, disagreement and differences practice models among physicians and other healthcare team members, perception of futile care and unnecessary suffering, family unrealistic expectation |

| Ganz and Sapir (2019) [27] | To describe perceptions of Israeli ICU nurses about end-of-life nursing care (include palliative care), the intensity and frequency of barriers to providing quality end-of-life care and the correlation between them | Quantitative approach with personal and work characteristics questionnaire, the quality of palliative care in the ICU And a revised ICU version of the survey of oncology nurses’ perceptions of end-of-life care (sonpelc) | Israel | General/medical, respiratory/surgical, cardiovascular and neurological ICUs | Nurses from 2 hospitals | 124 ICU nurses | Barriers providing end of life care in ICU such as communication between family, physicians and patients, and cultural differences leading to a lack of end-of-life discussions, and lack of palliative care education |

| Graw et al. (2012) [29] | To know advance directives influenced decision making of EOL on the ICU | Retrospective study | Germany | Surgical ICUs | Patients with terminal illness | 224 Patients | Lack of communication and inadequate of documentation being challenges in providing end of life care |

| Kyeremanteng et al. (2020) [19] | To explore barriers towards palliative care-ICU integration | Online survey through email | Canada | Cardiac ICUs | Physicians (n=16), nurses (n=154), ICU fellow (n=5), palliative care staff physician (n=6) | 181 Health workers | unrealistic patient or family expectations, disagreement about goals of care, different opinion of physician, and lack of communication skills as barriers to providing palliative care in ICU |

| Festic et al. (2012) [20] | To explore the differences of physicians and nurses on EOLC in the ICU and how these differences vary according to self-reported proficiency level and primary work unit | A cross-sectional study | United States | Adult ICUs | Physicians (n=50) and nurses (n=331) | 381 Health professionals | Significant differences between physicians and nurses were noted in the following areas: ability to safely raise concerns, DNR decision making, discussion of health care directives, timely hospice referral, spiritual assessment documentation, utilization of social services, and the availability of EOLC education. In every domain of EOLC, physicians reported a more positive perception than nurses. Additional differences were noted among physicians based on experience, as well as among nurses based on their primary work unit and self-reported proficiency level. |

| McKeown et al. (2011) [21] | To explore in depth the Stirling Royal Infirmary ICU team’s views and experiences of the difficulties of providing palliative care in an intensive care setting, and identification of the dying patient | Qualitative interview-based study | Scotland, United Kingdom | Adult ICUs | Participants consisted of consultants (n=5), nursing staffs (n=10) and junior medical staffs (n=10), none of who were known to the interviewing researcher in advance | A total of 25 interviews were undertaken | The ICU team reported there to be a number of advantages to providing EOLC in the ICU in terms of access to nursing and medical care. They also reported there to be issues surrounding training, identification of palliative care patients and over-aggressive management. Further collaboration between ICU and palliative medicine is required to develop understanding between the two specialties and expand provision of palliative care in this unique clinical setting. |

| Friedenberg et al. (2012) [22] | To identify training- and discipline-based barriers among ICU nurses and physicians in attending training | Survey | United States | Medical ICUs | Residents (n=125), fellows (n=20), attendings (n=13), and nurses (n=60) | 218 Participants | There were significant differences in reported barriers to EOL care by level of training, discipline, and institution, particularly in the education-training domain. Nurses’ perceptions of barriers to EOL care varied between institutions. Barriers that varied significantly between nurses included difficulty communicating due to language, inadequate training in recognition of pain and anxiety |

| Atwood et al. (2014) [28] | To compare oncology and CCPs' attitudes regarding palliative care | Electronic survey assessed using simulated patient description to identify respondents’ opinions of whether, when, and why palliative care should be utilized | United States | General ICU in academic hospitals | CCP (n=80), age ranged: 31–>60, years of experience 0–20 years, oncologist (n=72) | 152 Professionals participated | The trained CCP were more likely to integrate PC based on patients' risk and morbidity. |

| Women were more likely to incorporate PC in earlier the illness trajectory. | |||||||

| Attia et al. (2013) [23] | To investigate critical care nurses’ perceptions of barriers and supportive behaviors in providing EOL care to dying patients and their families. | Descriptive design | Egypt | Oncology, cardiology, hepatic and surgical ICUs | Nurses who involved in caring for critically ill patients | 70 ICU nurses | Several barriers were perceived: environment; family members, nurses’ knowledge and skills, physicians’ attitudes and treatment policy. |

| Oncology ICU (n=20) | |||||||

| Cardiology ICU (n=15) | |||||||

| Hepatic ICU (n=15) | |||||||

| Surgical ICU (n=20) | |||||||

| Bluck et al. (2019) [24] | To identify perspectives of HCP at EOL in ICU and barriers to provide palliative care | Mixed method approach: open ended survey | United States | ICU | Resident and fellows (n=18), | 39 Participants | Barriers providing palliative care in ICU included lack of care coordination, limited time, excessive paperwork, having a narrow knowledge base. |

| nurses (n=10), | |||||||

| attending physicians (n=6), | |||||||

| advanced practitioners (n=2), quality improvement specialist (n=2), case manager (n=1) | |||||||

| Ozga et al. (2020) [25] | To understand barriers to EOLC in ICUs, and to identify difficulties perceived by ICU nurses providing EOL care in Poland | Qualitative approach | Poland | Adult ICUs | The participants of the study included register nurses from various ICUs from across Poland with at least 2-year experience working at an ICU | 31 Individuals participated | The main issues raised during the interviews included (1) barriers attributable to the hospital, (2) barriers related to the patient’s family, and (3) barriers related to the ICU personnel providing direct EOLC. The interviewed nurses considered the lack of support from managers to be the main barrier. We found that ICU nurses in Poland dealt with end-of-life aspects that were emotionally and psychologically taxing. In addition, they lacked specialized training in this area, especially with regard to family care and care provision. |

| Silveira et al. (2016) [26] | To know the feelings of nurses regarding palliative care in adult intensive care units | Qualitative approach | Brazil | ICU | Participants of this study consisted of female (n=26) and male (n=4) nurses exercising their labor activities in the period of data collection and have at least one year experience in assisting adult palliative care patients in ICU, which may be current or past experience | 30 Nurses participated in this study | The results showed how central ideas are related to feelings of comfort, frustration, insecurity and anguish, in addition to the feeling that the professional training and performance are focused on the cure. |

| Sharour et al. (2019) [30] | To explore the obstacles and strategies for improvement from nurses' perception of EOLC | Quantitative study with a multisite cross-sectional descriptive design | Jordan | ICU | critical care nurse from different governmental and private hospitals | 163 Critical care nurses | The highest obstacles from the nurses’ perception were family and friends who continually call the nurse wanting an update on the patient’s condition rather than calling the designated family member for information. Furthermore, the highest three supportive behaviors from the nurses’ perception were physicians agreeing about direction of patient care, family members accept that patient is dying, family designating one family member as contact person for the rest of the family. |

- 1. Mercadante S, Gregoretti C, Cortegiani A. Palliative care in intensive care units: why, where, what, who, when, how. BMC Anesthesiol 2018;18:106. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 2. Yosick L, Crook RE, Gatto M, Maxwell TL, Duncan I, Ahmed T, et al. Effects of a population health community-based palliative care program on cost and utilization. J Palliat Med 2019;22:1075-81.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Hua M, Wunsch H. Integrating palliative care in the ICU. Curr Opin Crit Care 2014;20:673-80.ArticlePubMed

- 4. Munro CL, Savel RH. Aggressive care AND palliative care. Am J Crit Care 2018;27:84-6.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 5. Ito K, George N, Wilson J, Bowman J, Aaronson E, Ouchi K. Primary palliative care recommendations for critical care clinicians. J Intensive Care 2022;10:20. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 6. Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2014;42:2418-28.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Pan H, Shi W, Zhou Q, Chen G, Pan P. Palliative care in the intensive care unit: not just end-of-life care. Intensive Care Res 2022;1-6.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 8. Ganz FD, Ben Nun M, Raanan O. Introducing palliative care into the intensive care unit: an interventional study. Heart Lung 2020;49:915-21.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Hua MS, Li G, Blinderman CD, Wunsch H. Estimates of the need for palliative care consultation across united states intensive care units using a trigger-based model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:428-36.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. Coelho CB, Yankaskas JR. New concepts in palliative care in the intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2017;29:222-30.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Nielsen EL, Curtis JR. Palliative care for patients dying in the intensive care unit with chronic lung disease compared with metastatic cancer. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:684-9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Metaxa V, Anagnostou D, Vlachos S, Arulkumaran N, Bensemmane S, van Dusseldorp I, et al. Palliative care interventions in intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 2021;47:1415-25.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467-73.ArticlePubMed

- 14. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19-32.Article

- 15. Khalil H, Peters M, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Parker D. An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2016;13:118-23.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 16. Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020.

- 17. Santos DC, da Silva MM, Moreira MC, Zepeda KG, Gaspar RB. Care planning for patients receiving palliative care in an oncology intensive care unit. Acta Paul Enferm 2017;30:295-300.Article

- 18. Espinosa L, Young A, Symes L, Haile B, Walsh T. ICU nurses' experiences in providing terminal care. Crit Care Nurs Q 2010;33:273-81.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Kyeremanteng K, Beckerleg W, Wan C, Vanderspank-Wright B, D'Egidio G, Sutherland S, et al. Survey on barriers to critical care and palliative care integration. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;37:108-16.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 20. Festic E, Wilson ME, Gajic O, Divertie GD, Rabatin JT. Perspectives of physicians and nurses regarding end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 2012;27:45-54.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 21. McKeown A, Booth MG, Strachan L, Calder A, Keeley PW. Unsuitable for the intensive care unit: what happens next? J Palliat Med 2011;14:899-903.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Friedenberg AS, Levy MM, Ross S, Evans LE. Barriers to end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: perceptions vary by level of training, discipline, and institution. J Palliat Med 2012;15:404-11.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Attia AK, Abd-Elaziz WW, Kandeel NA. Critical care nurses' perception of barriers and supportive behaviors in end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013;30:297-304.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 24. Bluck S, Mroz EL, Baron-Lee J. Providers' perspectives on palliative care in a neuromedicine-intensive care unit: end-of-life expertise and barriers to referral. J Palliat Med 2019;22:364-9.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Ozga D, Woźniak K, Gurowiec PJ. Difficulties perceived by ICU nurses providing end-of-life care: a qualitative study. Glob Adv Health Med 2020;9:2164956120916176. ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 26. Silveira NR, Nascimento ER, Rosa LM, Jung W, Martins SR, Fontes MD. Palliative care and the intensive care nurses: feelings that endure. Rev Bras Enferm 2016;69:1074-81.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Ganz FD, Sapir B. Nurses' perceptions of intensive care unit palliative care at end of life. Nurs Crit Care 2019;24:141-8.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 28. Atwood MA, Hoffmann RG, Yan K, Lee KJ. Attitudes about palliative care: a comparison of pediatric critical care and oncology providers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:665-71.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 29. Graw JA, Spies CD, Wernecke KD, Braun JP. Managing end-of-life decision making in intensive care medicine: a perspective from Charité Hospital, Germany. PLoS One 2012;7:e46446.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Sharour LA, Subih M, Salameh O, Alrshoud M. End-of-life care (EOLC) in Jordanian critical care units: barriers and strategies for improving. Crit Care Shock 2019;22:88-97.

- 31. Riegel M, Randall S, Ranse K, Buckley T. Healthcare professionals' values about and experience with facilitating end-of-life care in the adult intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021;65:103057.ArticlePubMed

- 32. Albert M, Herlitz J, Rawshani A, Ringh M, Claesson A, Djärv T, et al. Cardiac arrest after pulmonary aspiration in hospitalised patients: a national observational study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e032264.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 33. Edwards JD, Voigt LP, Nelson JE. Ten key points about ICU palliative care. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:83-5.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 34. Mathews KS, Nelson JE. Palliative care in the ICU of 2050: past is prologue. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:1850-2.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 35. Price DM, Strodtman L, Montagnini M, Smith HM, Miller J, Zybert J, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care education needs of nurses across inpatient care settings. J Contin Educ Nurs 2017;48:329-36.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, Galusca D, Smith TJ, Pronovost PJ. Evidence-based palliative care in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of interventions. J Palliat Med 2014;17:219-35.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 37. Brooks LA, Manias E, Nicholson P. Barriers, enablers and challenges to initiating end-of-life care in an Australian intensive care unit context. Aust Crit Care 2017;30:161-6.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Kalies H, Schöttmer R, Simon ST, Voltz R, Crispin A, Bausewein C. Barriers for the implementation of guidelines in palliative care-results from a national survey of professionals. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1943-52.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 39. Hall JB. Making recommendations for limiting care in the ICU based on sound prognosis. JAMA 2017;317:2170-1.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Mani RK, Amin P, Chawla R, Divatia JV, Kapadia F, Khilnani P, et al. Guidelines for end-of-life and palliative care in Indian intensive care units' ISCCM consensus ethical position statement. Indian J Crit Care Med 2012;16:166-81.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Almansour I, Seymour JE, Aubeeluck A. Staff perception of obstacles and facilitators when providing end of life care in critical care units of two teaching hospitals: a survey design. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2019;53:8-14.ArticlePubMed

- 42. Lind R. Sense of responsibility in ICU end-of-life decision-making: relatives' experiences. Nurs Ethics 2019;26:270-9.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 43. Graham R, Lepage C, Boitor M, Petizian S, Fillion L, Gélinas C. Acceptability and feasibility of an interprofessional end-of-life/palliative care educational intervention in the intensive care unit: a mixed-methods study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2018;48:75-84.ArticlePubMed

- 44. Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Myatra SN, Chan YH, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in intensive care units in Asia. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:363-71.ArticlePubMed

- 45. Phua J, Joynt GM, Nishimura M, Deng Y, Myatra SN, Chan YH, et al. Withholding and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in low-middle-income versus high-income Asian countries and regions. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:1118-27.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 46. Tripathy S, Routray PK, Mishra JC. Intensive care nurses' attitude on palliative and end of life care. Indian J Crit Care Med 2017;21:655-9.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 47. Jang SK, Park WH, Kim HI, Chang SO. Exploring nurses' end-of-life care for dying patients in the ICU using focus group interviews. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2019;52:3-8.ArticlePubMed

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- A necessidade dos cuidados paliativos na Unidade de Terapia Intensiva (UTI)

Larissa Kênia de Oliveira Barros Dos Santos, Isabella Rodrigues Ribeiro, João Pedro Manduca Ferreira, Victor Hugo Oliveira Moraes, Érika Aguiar Lara Pereira

Cuadernos de Educación y Desarrollo.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - End-of-life Care in the Intensive Care Unit and Ethics of Withholding/Withdrawal of Life-sustaining Treatments

Andrea Cortegiani, Mariachiara Ippolito, Sebastiano Mercadante

Anesthesiology Clinics.2024; 42(3): 407. CrossRef - What helps or hinders effective end-of-life care in adult intensive care units in Middle Eastern countries? A systematic review

Nabat Almalki, Breidge Boyle, Peter O’Halloran

BMC Palliative Care.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Patterns of care at the end of life: a retrospective study of Italian patients with advanced breast cancer

Irene Giannubilo, Linda Battistuzzi, Eva Blondeaux, Tommaso Ruelle, Francesca Benedetta Poggio, Giulia Buzzatti, Alessia D’Alonzo, Federica Della Rovere, Maria Maddalena Latocca, Chiara Molinelli, Maria Grazia Razeti, Simone Nardin, Luca Arecco, Marta Per

BMC Palliative Care.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit: The Standard of Care

Clareen Wiencek

AACN Advanced Critical Care.2024; 35(2): 112. CrossRef - Healthcare Professionals’ Attitudes towards and Knowledge and Understanding of Paediatric Palliative Medicine (PPM) and Its Meaning within the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU): A Summative Content Analysis in a Tertiary Children’s Hospital in Scotlan

Satyajit Ray, Emma Victoria McLorie, Jonathan Downie

Healthcare.2023; 11(17): 2438. CrossRef

KSCCM

KSCCM

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite